.44 OR .45?

When these two numbers are put together, people usually sit up and pay attention. John Wayne stands tall with his ‘Colt 45’ and Clint Eastwood faces off with his ‘S&W 44 Magnum’.1 There’s only a hundredth of an inch separating the two calibers, and a generation of contention as to which is the finer round or revolver. The number 45 can be flipped to make 54 and pleasure seeking Baby Boomers come to mind, singing along with the Village People’s iconic tune YMCA against the backdrop of Studio 54, New York’s iconic 70’s disco. So what happens in the brain when it hears something so reduced in size and economical in its symbolism as two numbers, juxtaposed either forwards or backwards?

For all of the Steampunk cogwheels and curly-cues of the Victorian age, cartridges and bullets are amongst the most abstract shapes to come out of the Industrial Revolution, a perfect union of straight line and curve.2 From the outside, a cartridge is haunting in its reduced simplicity: little more than a truncated cylinder of gleaming brass filled with gunpowder, into which is wedged a lead bullet. The nose cone of a bullet is a round ogive shape, designed to slice through wind with optimum efficiency. Yet for all its modernist austerity, a bullet is pregnant with the capacity for a life changing, visceral, nasty, messy, causality. Who would have known that such ghastly termination could be born from such pure form? The clue is the ear-splitting crack-bang that accompanies each shot. The raw power of that noise, whose only parallel in nature is a thunderclap, feels like all the noises of the world have been compressed into a split second. Surely that alone tells us something. And not to be forgotten is that when the chips are down, the cartridge becomes currency, not worthless paper money. The real price of life is unambiguously mirrored in the simple form; one is exchanged for the other.3 What we know today as a ‘bullet shape’ started out as a perfectly round sphere of lead used for centuries in matchlock, wheel lock and flintlock muskets and pistols up until the 1830s. Keplarian globes would sail through the air in constellations from massed volleys of smoothbore muskets, from the ranks of British Red Coats and American Revolutionaries alike. The leaden balls would yaw and arc through space, inaccurate and going their own way, hoping for a chance hit upon their unfortunate adversary. The balls were big, slow and heavy, between one-half and three-quarters of an inch in diameter. A musketeer, if his view was unsullied by smoke, could watch the unhurried passage of the ball form a shallow parabolic arc as it wended its way into the heart of darkness. Basic military ammunition is still called Ball ammo, despite no longer being spherical.

A .69” diameter lead sphere of lead bullet was easily dropped down the muzzle of smoothbore muskets, as their diameter was smaller than that of the .75 Cal. Brown Bess barrel. They were by no means perfect spheres and a further diminishment in accuracy occurred when the casting sprue was snipped off by the soldier.

Collection of the author

It may be wondered why some of the standard ammunition we know today, such as .44, .36 and .32 calibers. have such seemingly irregular dimensions. The reason is deceptively simple. The standard .75 Caliber Brown Bess of the 1776 Revolutionary War musket used a .69 caliber ball and weighed approximately 1¼ ounce or thirteen to a pound. The table below shows the relative weights of smaller ammunition.4

| Caliber | Approx. number to 1 pound | Approx. relative size |

|---|---|---|

| .69 (.68) | 13 | 1 |

| .58 (.57) | 25 | 1/2 weight of .69 |

| 44 (.453) | .50 | 1/2 weight of .58 |

| .36 (.375) | 100 | 1/2 weight of .44 |

| .31 (.320) | 150 | 1/3 weight of .36 |

| .28 (.265) | 250 | 1/5 weight of .31 |

The diameter of ball ammunition began to diminish when barrels could be inexpensively rifled, as an accurate shot is more deadly although the ball is smaller. When Samuel Colt patented his revolver mechanism in 1836, a new search for the right caliber ball ammo was set in motion. The Colt Paterson .36 cal. revolver, considered by many to be one of the most elegant handguns ever made, could fire five shots in quick succession. For the nascent gun industry, the search was on for a revolving handgun that was the right mix of firepower, caliber, lightness and ease of manufacture to reliably deliver more shots on target if the first one missed.5

One of America’s finest collections of Colt Paterson revolvers, as well as many other Colt pistols, is at the Woolaroc Museum off the beaten path in rural Oklahoma. The Colt Firearms Museum, within the Connecticut State Library, could make the same claim. To give a sense of their epicurean rarity, in 2011 a Colt Paterson sold for $977,500. When visiting Los Angeles, another great collection of Colt Patersons is at the Gene Autry Museum, home of the “Singing Cowboy”. This Los Angeles museum has a premier collection of revolvers embellished by the very best 19th century German-American engravers. For anyone interested in art & technology, the Greg Martin Gallery in the Autry Museum is a must--see place.

Photo permission, Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

This almost new (98%) reproduction was made by Pietta, and was bought at a gun show for $75. Firearm research starts at gun shows where, unlike museums, everything can be handled without kid gloves and there is a wealth of shared knowledge at hand. Gun shows are largely “cash & carry” affairs in which attendees and amateur sellers carry wads of $100 bills, peppered by $20s. Professional dealers require a background check to complete the transaction for any gun made after 1898. NOT SO THE amateur dealer. For firearm collector/scholars, a gun show is about as much fun as can be had for a $10 entry fee and, although I hate to say it, it is AS equally interesting as an art museum.

Collection of the author.

The barrel and fore-frame are made from one piece of steel and sculpted for maximum economy of weight. Its androgynous form was manufactured either by casting, milling machines or by being forged: the curved cuts are considered to be a marvel of technology wedded to art.

Photo permission of the Colt Firearms Museum, Museum of Connecticut History

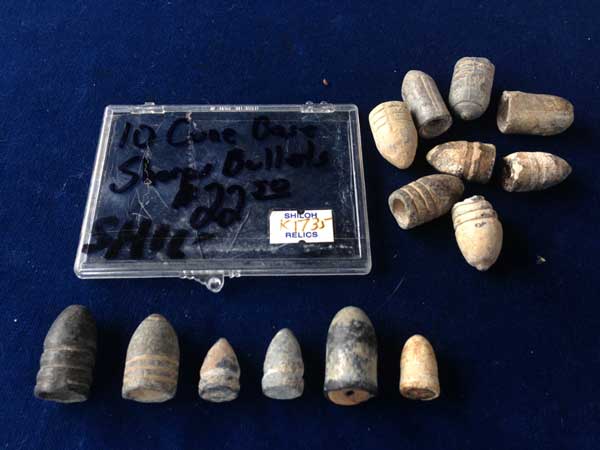

Civil war bullets are miracles of design, having some of the most minimalist profiles of the 19th century. The bullet on the bottom row on the right is a rare .41 cal. round for the Volcanic Pistol, based on the design concept of Hunt’s ‘Rocket Ball’. The powder charge is in the hollow of the lead bullet, as is the percussion cap, dispensing with the need for a copper cartridge shell. The Volcanic pistol was so underpowered that it was ineffective at anything but close range, but the design gave birth to the Henry 1860 ‘Yellow Boy’ and 1873 Winchester lever action rifles. This Volcanic round was found on a Civil War battlefield in a cache of twelve unused examples, implying that they were dumped, dropped or fell with a soldier. Good archaeological practice could have answered that question; something that a metal detector is not programmed to do.

Collection of the author

The problem with lead balls and loose black powder wrapped in cartridge paper was that they were slow to load and susceptible to misfire during rain, a situation made marginally better by the invention of the percussion cap ignition system. The second problem with paper cartridges was that breech-loading guns could have a gap between block, breech and barrel through which the explosive gasses escaped.

The pinfire cartridge was perfected by Eugène Lefaucheux, on his father Casimir Lefaucheux’s 1837 patent. The Flobert 6mm (.22 BB Cap) is the first metallic waterproof cartridge with primer, propellant and bullet contained in a copper shell. Later versions added gunpowder to increase the muzzle velocity, although Flobert had inserted that eventuality in his 1849 patent. Collection of author.

Collection of author.

Gilles Mariette made the barrel for this Houllier Blanchard pistol; Mariette was a Belgian gunsmith of great inventiveness, having patented the double action pepperbox revolver in 1837. Houllier was of equal stature, and held patents on cartridges. “Flobert” parlor pistols are transitional firearms, the first guns to use fully contained wedge-shaped waterproof cartridges; they were not rimmed, as are the modern versions shown here. Early Flobert pistols made the large hammer double as a breechblock. Later versions used a complicated three-piece mechanism known as the ‘Remington System’, with separate parts for extraction, a breechblock and a hammer. There is scant literature on Flobert pistols and you find them in unusual places and often mis-cataloged. Parlor pistols were originally used for indoor target practice; they are still used in Europe, as stringent firearm laws do not regulate the cartridge. In his book The Banquet Years Roger Shattuck described Parisian intellectuals entertaining themselves with guns in cafes; one particularly good marksman could shoot the pipe from an unsuspecting tippler. It was probably done with a Flobert.

Collection of author.

The Whitneyville ‘Model 1 was based on the S&W Number 1, whose 1855 S&W patent had expired in 1872 after seventeen years of protection. The Whitneyville was made by the Whitney family who developed the machine tools that set in motion the “American System” of making identical and interchangeable components. Smith & Wesson had perfected Flobert’s all-in-one cartridge design with the “The Smith & Wesson No 1 cartridge”, known today as the .22 Short, for which S&W added a rim to aid its seating in the cylinder as well as extraction. Although diminutive, it is a lethal round. When shot in the 1860’s, the wounded were likely to die of infection. The .22 Short, loaded with black powder, was the first American rim fire cartridge invented and has been in continuous production since 1857. Few, if any, designed objects of the Industrial Age have lasted unchanged for one hundred and fifty-eight years. Remarkably, later versions of the S&W Model 1 revolver can still be bought for under $300. This one was chosen by the author because of its association with a branch of the Whitney family, of Whitney Museum of American Art fame. Art and technology, as well as war and peace, are never far apart.

Note: the modern.22 Shorts in the photograph use smokeless powder and are loaded too ‘hot’ for this gun, and could blow out the cylinder!

Collection of author.

Fig 10b .44 cal. and .44 Henry Rimfire cartridges.

This rifle was presented to David Reed, sometime after 1863, after being wounded. He fought at Gettyburg. The Henry 1860 Repeating Rifle and .44 Henry rimfire cartridges were designed together as one synonymous system. The Union Army bought over 4.6 million rounds of Henry ammunition. Collecting ammunition is compelling if only because the forms are aesthetically beautiful, a perfect wedding between straight-line and curve, as you would expect for an object that flies through the air at great speed. To have in your hand something so small, yet so terminally momentous, is sobering. One wonders how an object, as perfect in shape as an egg, could wreak such explosive havoc. Today, the universal availability of ammunition outside of America’s cities is ubiquitous: it lies in stores on open shelves in stacks, as if it were no more consequential than cans of beans.

Fig. 10a Photo courtesy of the Frazier History Museum

Fig. 10b Cartridges collection of the author.

The development of the rimfire cartridge is as complicated as it is fascinating, and shows an evolution of design that is as thrilling and high-stakes as any. In addition to inspecting prototype and production cartridges in person, it requires following French and American patent development for both ammunition and firearm designs that weave in and out between revolver and repeating arms inventions.12 In the US, Smith & Wesson were developing two kinds of ammunition; the case-less .31 or .41 ‘Volcanic’ and the metallic case .22 ‘Short’. Initially the Smith & Wesson Magazine Pistol (the ‘Volcanic’) was designed for metallic case ammunition, but for production in 1853 the case-less ‘Volcanic’ round was chosen, probably because the technique of manufacturing the metal case had not been perfected. The Volcanic was an underpowered design that was not effective and the business failed. A new company was formed and the S&W Model I revolver was brought out in 1857 by which time a successful .22 rimfire cartridge could be manufactured. In 1860 the mechanism of the Volcanic repeater and a .44 rimfire cartridge, perfected by B. Tyler Henry, were wedded together to make the 1860 Henry Rifle. B.T. Henry designed and built the first effective machinery of the mass production of metallic cartridges.13 But Smith & Wesson were not the beneficiaries of the ground-breaking lever-action rifle. Yhat would be the prize of Oliver Winchester, its new financial backer.14

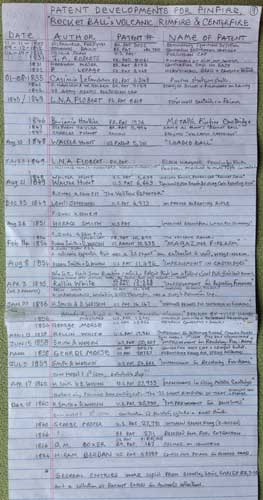

Notes of the author.

By the time the rimfire cartridge had been perfected, and before the centerfire cartridge had come into being, all of the essential elements of the modern day cartridge had been identified: the optimal bullet size, the right quantity of powder and a reliable percussion system brought together in one waterproof metallic package. Developers of cartridges negotiate between many parameters to achieve greatest efficiency, and juggling these factors is nothing short of a ‘design dance’. Today the outcome of these design decisions is quantified by standardized expressions of performance. The weight of the bullet is expressed in ‘grains’, as is the powder that propels the bullet. The outcome of the right combination of these two variables is expressed as the ‘muzzle velocity’, expressed in ft/s or m/s (metric), meaning the speed of the bullet measured in feet per second when it leaves the barrel of the gun. The power of a bullet is called the ‘muzzle energy’, meaning the kinetic energy of a bullet expressed in ft-lbf or joules (metric). A very heavy bullet moving slowly can have similar destructive energy as a light bullet moving fast; naturally the energy decreases with distance as the bullet slows, which is why the aerodynamics of the bullet counts. But these are not the only factors in the performance of a cartridge. Black powder left considerable a 40% residue in the barrel that literally jammed up the works and made the gun inoperable after a number of shots. This led to another design advance, the addition of incised rings in the lead bullet into which grease was inserted to lubricate the bullet as well as help clean the barrel of residue. The design of gunpowder is also critical, and chemists in each country worked hard to create more efficient and more stable but slower burning “smokeless” powders producing a greater volume of propellant gasses and much less residue.15 This had a huge impact on the ‘design dance’ of the cartridge, as well as the design of the rifle’s barrel length for if all the powder has not been burned by the time the bullet leaves the muzzle of the gun, powder and energy is wasted. And if the barrel is too long it becomes unwieldy and if too short it becomes inaccurate. Another consequence of smokeless powder was that the lead of the faster moving bullet was deposited in the barrel. This unforeseen problem resulted in a new design-development to coat the bullet in copper, leading to the Full Metal Jacket (FMJ) bullet. The design dance constantly shifts with each advance of technology. The design of a cartridge is every bit as time-consuming and complex as the design of the gun that fires it, and is why some of the most successful cartridges and firearms were designed together as one system. The optimal balance between the two can be equated to the design of ‘hardware’ and ‘software’ in computer design, and has equal consequence.

Ammunition went through its next big evolution with the invention of the centerfire cartridge. It used a modified percussion cap called a ‘primer’, set into the base of a brass shell to ignite the black powder. This development quickly made rimfire ammunition obsolete, except for the .22 cal. round. In 1866 and 1869, patents were issued for the Berdan No. 1 primer and the Boxer primer, proprietary variations of a small disposable copper cup filled with mercury fulminate that ignites when struck with a hammer. The new primers were wedged into the base of a metallic cartridge and designed to be easily replaced, meaning that the brass shell could be reused several times. This was a vitally important design-development. Living on the Western Frontier required that you recycled your own ammunition from a collection of brass shells, replaceable primers, a can of black powder and a bag of lead bullets. It was an early example of recycling mechanical parts in the Industrial Age. A trip to Wal-Mart to stock up on ammo was a distant concept at that time. In Great Britain, .450 cal. black powder centerfire cartridges were introduced in 1868 for the Adams revolver. The more powerful .455 cartridge was developed for the 1887 Webley Mk. 1 revolver. In America, the large-frame Smith & Wesson Number 3 revolver of 1869, generically known today as the ‘Schofield’, used the new .44 cal. American centerfire cartridge.16 The revolver’s top-break design, coupled with the new star-ejector, meant that you could eject all spent shells simultaneously, resulting in very fast reload times. It was a revolutionary design. Four years later, Colt introduced the legendary Model 1873 Single Action Army revolver, the ‘Colt 45’, designed specifically to shoot their proprietary .45 Colt cartridges. These were 40% more powerful than the .44 S&W American cartridge. The Colt .45 used 35 grains of black powder rather than 23 grains for the Smith & Wesson .44. It should be added here that the .44 S&W American, Russian, Special and Magnum cartridges all use bullets of a nominal diameter of .429”. Smith & Wesson were alert to good advertising and probably used the moniker ‘44’ to take full advantage of the catchy name of the number, that is so closely associated with their brand.17

A brilliant design that introduced the top break and star-ejector, but it lost out to the Colt SAA .45 cal. in the US. Perhaps it was based on looks because, let’s face it, this one is a bit dumpy. Its lack of success was more likely due to intransigence on the part of S&W, to not accommodate their competitor Colt’s more powerful .45 cartridges by adding a lengthened cylinder & frame, although they did do that for the .44-40 cartridge. Corporate pissing matches equate to the fight at O.K. Corral or a couple of professors staking their careers in the classroom. In animalistic displays of predator & prey, each can end with winners and losers. This particular S&W is from the Davis Museum in Oklahoma, a treasure trove of 13,000 guns, kept in a Bruto-Modernist concrete box. They are arranged in custom built black-painted steel cases fitted with pegboard and lit by neon. The architects Prouvé, Breuer and Mies would have been proud of their influences, in equal measure.

Photo Ben Nicholson, courtesy J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum, Claremore, OK.

From the emotive point of view, this revolver, known as a “Hog’s Leg,” has been lying on my worktable for the past four days, migrating from one spot to another. It is photographed on top of a MacBook Pro, belonging to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a perfect backdrop. I ask myself over and over again, “Why is the design so compelling?” Certainly it is the gun of boyhood dreams, of lying on the floor in front of the neighbor’s telly watching the Lone Ranger in the 1960s, but surely that is not enough to irrigate my aesthetic imagination alone. Do we dare admit, in this age of equal opportunity, that there is such a thing as beauty and “Getting it right,” where all parts are in perfect harmony? The long tube attached to the side of the barrel is both counterintuitive and ugly, yet the revolver would not get a gazillion “likes” without it. From a technical point of view, the Colt Single Action Army was made with the same machinery used for the Model 1860 percussion revolver and some of the parts interchange. (The Colt factory burned in 1862 and the machinery was all in good condition, having been made in 1863.) The designer William Mason changed the cylinder and frame, adding a top strap (U.S.Pat. 51,117, Nov 21 1865), a housing for the ejector rod and a loading gate (U.S Pat. 158,957 Jan 19 1875). The barrels were rifled with the same machinery. In both cases, the groove diameters are .451”. So the .45 really is a .45.18

Collection of the author.

What exactly is ammunition and firearm scholarship within academia, and how does it differ from the practice of a knowledgeable collector? For one thing, a scholar cannot take guns or ammunition into their office at a university or design school, at least not in the North, so that makes study impracticable. Taboo follows closely on its heels. There are tens of thousands of different kinds of cartridges, each a different design in some respect, and they need to be in your hand to examine them fully. By studying the aerodynamics, metallurgy, chemistry, techniques and location of manufacture, as well as the packaging, the faint changes between each development show the genius of invention in slow motion. Study of this pivotal aspect of the foundations of industrial design is logistically difficult and well neigh impossible for an urban student and academic alike.

Collection of the author.

Now that .45 Colt and .44-40 WCF cartridges were being used interchangeably between pistols and lever-action carbine rifles, a parallel development was occurring to redesign long rifles to take a more powerful black powder cartridge in an optimum caliber. It was determined that the new rifle ammunition should have between 70 to 100 grains of powder rather than 35 grains used in the .45 Colt revolver cartridge. To determine the correct caliber, in 1873 the Army set up an exhaustive “Small Arms Caliber” Board and tested a .40, .42 and .45 caliber bullet against the .50. They chose the .45.21 To address these two factors, a brass alloy shell was developed, elongated for more powder and greatly strengthened at its base. This effectively sealed the breech blocks of escaping gasses of the new trapdoor, falling block and lever-action designs. So was born the mighty .45-70 round, designed for the 1873 Springfield Trapdoor rifle, and using over double the powder of the revolver cartridge.

Large gun shows usually have a few tables at which cartridge collectors sell and trade their wares. For what they are and what the represent, the standard cartridges are remarkably inexpensive. $5 will secure a good example and $50 a remarkable piece. The IAA (International Ammunition Association) meets annually in St Louis for the St. Louis International Cartridge Show and is a human encyclopedia of shared knowledge on the subject. The rolled .450 is a Boxer Henry Long 2nd major version produced in 1868, the same year that Mauser introduced their drawn, single piece cartridge. The Mauser was an infinitely superior machine-made design that immediately eclipsed the Boxer Henry, which was kept in production due to a cheap labor force of young English girls who hand-assembled them.22

Collection of the author.

By the time the 19th century was drawing to a close, a whole new kind of mechanized warfare was in the wings, and weapons were being developed to fight them. The European powers were working on their own versions of the high-power smokeless gunpowder of the 1880’s, and in the USA DuPont and other manufacturers were developing smokeless powder. The .45 cal. black powder rifle had become a thing of the past. The new generation of rifles was designed for small, fast moving aerodynamic bullets in the .30” or 8mm diameter range, and they delivered more kinetic energy to the target than the heavy, slower-moving .45 bullets of the black powder era. For handguns, the powerful smokeless powder set in motion a new generation of design possibilities. There was now enough spare energy to operate the complex mechanical action of semi-automatic pistols being developed in Germany and America in the 1890’s. There was also a move towards the smaller .38 and 9mm cal. Cartridges. The increased speed from these new propellants equaled the kinetic energy of the large but slow moving revolver rounds, and were calculated to have equal stopping power. However, Western armies found the smaller caliber fine for incapacitating people of European stock, but when it came to suppressing their imperial subjects, particularly the Moro Warriors of the Philippines – hardy soldiers reputedly cranked up on drugs – the .36 and 38 caliber pistols were deemed to be underpowered. To solve the problem, the Springfield Arsenal reworked the Army’s obsolete Colt SAA .45s and sent them (as Artillery Models) to the Philippines with smokeless powder ammunition. The heavier round worked.

The left-hand cartridge was made in 1912, one year after its introduction in 1911. Both cartridges are FMJ (Full Metal Jacket) a requirement of the Geneva Convention that disallows lead bullets or soft tipped bullets as they are seen to cause inhumane damage. Paradoxically the red Teflon tipped round, which expands upon impact, is legal to use in the United States by both Law Enforcement agencies and civilians alike, but not by the U.S. Army overseas.

Collection of the author.

Spooked by the Moro Warrior episode, in 1907 the U.S. Army put out a call for a new sidearm that would return to large caliber .45 cal. cartridges.23 The new round had to be rimless so that it could be used for semi-automatic pistols. In one of the most interesting competitions ever held, the major gun makers of Europe and America were pitted against each other to produce the next official side arm for the US Army. The requirement was that it should be powerful enough to fell any foe with one shot to the torso at standard distances. Ten companies entered and the finalists included Colt, Luger and Savage, who had all upsized their smaller .32 or 9mm caliber pistols, developed in the 1890’s, to take the new .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridge designed by John Browning.24 Colt had the advantage of Browning designing both the .45 ACP round as well as the Colt .45 semi-auto pistol, and it was thought that Colt’s submission had an unfair advantage. There was the accusation, unfounded, that Colt had put less powder in the competitor’s ammunition so that their actions would not cycle properly. In a pissing contest of epic proportions, hundreds of rounds were run through each gun in a torture test and Colt came out victorious.

The Luger P-08, 9mm and Savage 1907 .32ACP illustrated here are in their original calibers before they were up-scaled for the .45 ACP cartridge. These “Trials” pistols in .45 are immensely rare as very few were made. The stainless steel Colt 1911 Government Model Series 80 .45ACP was bought by the author in 2011, and is marked “100 years of service” to commemorate the pistol’s 100th year anniversary. This particular Luger P-08 was made in 1936, at the pinnacle of its technological refinement, prior to the commencement of wartime production when standards were lowered. The Savage 1907 was a groundbreaking design, the first pistol to be held together with steel pins rather than screws and to have a double-stack magazine for ten rounds in the grips. This Savage 1907 is version 17 Model 2 and recognized to be mechanically the best of the seventeen versions produced.

Collection of the author.

The Colt 1911 heralded the third act in the saga of the .45 caliber. It signaled the birth of a new cartridge for a pistol that has become one of the two most famous handguns America has ever produced, both in .45 caliber. The Colt 1911 was accepted by the Army the same year that the Wright Brothers flew the 1911 Wright Model B Flyer but, unlike that particular airplane, the Colt 1911 has remained essentially unchanged for 100 years. It is a perfect, classic design and is still going strong. Thank you, John Moses Browning. Ten years later in 1921, the same .45ACP round was used for the Thompson submachine gun. Thank you, General John Thompson. A single round of .45ACP could be used in both a long gun and a handgun, thus simplifying the army’s ammunition supply.25 Once again, it repeated the concept of interchangeability of ammunition between handguns and long guns that the Colt SAA revolver and the Remington lever action rifle pioneered with the .44-40 cartridge. In 1985, the U.S. Army withdrew the Colt 1911A1 from general service and replaced it with the Beretta 92B, using a 9mm round. Interestingly, after the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, soldiers displayed dissatisfaction with the lighter 9mm round and the Army is apparently taking another look at the .45 cartridge, thus repeating a discussion between the .44 and .36 (9mm) families of ammunition. This will be the third time such a discussion has been held over the past 150 years.

There is no doubt that American western movies made during the Cold War were vastly influential in promoting the mythology of the .45 cartridge. John Wayne took many of the leading roles, brandishing his Colt SAA revolver that, unbeknownst to many, was just as likely to be chambered in .44-40 as .45. The genre of the American western was established in 1939 with John Wayne in Stage Coach, a tense and sultry movie, whose heroes are the American Cavalry who save the day from Apaches, a saga that shadows the build-up to WWII and America’s preeminence against the Axis armies. The scores of American and Italian Spaghetti Westerns made from the 1950’s to 1970’s are thinly veiled symbols of the showdown between the Good Kennedy and the Bad Khrushchev. The Colt .45 Single Action Army revolver was emblematic of the newly mythologized global power of the emerging American Empire, where sheriffs bring outlaws to heel and heroic settlers and soldiers slaughter the backward redskins. Now that tribal casinos have come on line, the tables have begun to turn – literally. America’s indigenous peoples are now slaughtering the wallets of the settlers to this continent, both old and new. Badda-bing, badda-boom!

The fourth incarnation of this family of cartridges is the .44 Magnum, the modern-day smokeless powder version of those of the 1870’s.26 With its redesigned brass shell, powder and bullet, the .44 Magnum is two to four times as powerful, or ‘hotter’, than the .44 and .45 cartridges of yesteryear. The magnum family of revolver cartridges was introduced in the 1930’s, during the gangster and bootlegging era, when the police needed a round that would shoot through sheet metal car doors. Starting with the .38 Super Auto and culminating in the .357 Magnum in 1934, the caliber was increased to .44 Remington Magnum in 1955 and then the .454 Casull in 1957. The .44 Mag was primarily designed for hunting big game. It is too potent for law enforcement as the bullet is just as likely to incapacitate the person standing behind the perp, as the perp him or herself. That is a bad situation for a policeman, but it didn’t deter Dirty Harry from using it for that purpose. The .44 Magnum cartridge has the same external dimensions as the original 1873 .45 Colt round, and was designed for the massive Smith & Wesson Model 29 revolver of 1959, which was Clint Eastwood’s ‘Dirty Harry’ gun of that movie’s name.

This S&W Model 29 was decorated for the S&W exhibit at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, following a long tradition of making the most artistically decorated gun for exhibition purposes. It was carved and gilded by Smith & Wesson’s Master engraver Russ Smith. He mirrored the style of Gustave Young who produced his greatest masterpiece, a Smith & Wesson New Model No. 3, for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Gone are the days when firearms are celebrated in a World Exhibition, for the intrinsic relationship between civic and military life is not so accommodating as it once was.

Photograph permission of Lyman and Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History. Springfield, Massachusetts. Photograph by John Polak (CVHM 98.00243)

Internet chat rooms indeterminably engage in a longstanding banter as to whether the .45 Colt or the .44 Magnum is the more iconic round, or if Colt’s ‘Snake’ revolvers are better than Smith & Wesson’s Model 29, the Dirty Harry ‘hand cannon’. The discussion runs along the same lines as to whether John Wayne or Clint Eastwood better define the American psyche, similar to the indeterminable bar-room arguments over whether a Ford or Chevy is better, or, in the lingo of this readership, a BMW 4 Series, an Audi A5 or Merc A45. Even here, 4 and 5 are once again the pivotal numbers, something that the marketing teams of the automobile industry are surely well aware of. Throughout the long history of both the .45 and .44 rounds, in practical terms the many incarnations of the .44 probably wins the prize. On the other hand, the mythology of the .45 has an unstoppable power in popular imagination. The aura of the .45 round tends towards the semantic rather than the scientific, and the .44 is historically more experimental. If there is a choice, which there often is, choosing the right caliber for a pistol is not an easy decision. Based upon the mystique and quality of invention of the .44 or the .45 cartridges, it would have to be the .44. Then again, with a little more thought, maybe the .45 will do the job just fine. When push comes to shove, no one would ever know the difference. It’s the medium, not the message, which stops people in their tracks. Copyright Ben Nicholson, October 7th 2015, New Harmony, Indiana.

1 The ‘Colt 45’ is the Colt Single Action Army revolver, Model of 1873, which used the .45 caliber Colt cartridge. The ’44 Magnum’ is the Smith & Wesson Model 29, that used the .44 Magnum cartridge.

2 The standard, non-specialized reference on historical and contemporary cartridge is Frank Barnes Cartridges of the World, 14th Edition, Gun Digest (2014). See also Michael Bussard 5th Ammo Encyclopedia, Blue Book Publications, Minneapolis, 2014. For a good but slightly quirky book on small arms ammunition read Herschel Logan’s Cartridges: A Pictorial Digest of Small Arms Ammunition, New York (1959). Logan was a woodcut artist who illustrated rural life Kansas, writer and avid cartridge collector. He combined these talents and made an easy to read, highly informative volume that he illustrated himself. It is worth noting that of the hundreds of excellent books on firearms and ammunition, I know of only two that are published by university presses, and is an indication of the refusal of academia to acknowledge firearms a valid subject of inquiry. Museums do produce excellent catalogs and bulletins on specialized subjects, some of which are referred to below.

3 My thanks to Richard LaVen, who made a very careful reading of this text. He noted that Martha Phillips Gilson (1896-1993 spent much of the years 1916-1928 in the high Arctic. She was a very accomplished photographer and her Arctic landscapes are still considered masterpieces. Martha was a practical cartridge collector and could identify almost anything common (from her era) at a glance. She explained "In the high Arctic, money had no value. Cartridges were the common denominator of barter or commerce. In North America, the most commonly accepted were .44-40s. After that .30-30s or either .303, .30-40 Krag or .30-06. In Greenland, the Danish centerfires or maybe Jarmanns. In Spitsbergen & Arctic Norway & Sweden, 6.5x55. Finland & east, usually 7.62 Russian. Telling them apart was no more difficult than making change in pounds, shillings & pence." Martha had little use for revolvers or their cartridges. "They won't kill a polar bear. A Krag will, but only just."

4 My thanks to Ken Meek, Museum Director of Woolaroc Museum, OK for pointing this table out, from the Dixie Gunworks website. Note that there is conflicting information about the weight of a .69 musket ball, which may skew this table. The most logical formula is that a .69 caliber ball of lead weighs 480 grains which equals 1 Troy ounce. An Avoirdupois ounce weighs 453.5 grains which equals 1.03 ounces. The differences between Troy and Avoirdupois ounces is infinitesimal, (much like the .44 and 45 caliber bullet) but it counts when weighing out gold. If the .69 caliber bullet is related to the Troy weight, this table may be wrong. The authority on ammunition of this period is Berkeley Lewis ‘Small Arms and Ammunition in the United States Service, 1776-1865’, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol.129, pp. 219-231, Washington DC, (1956) . On page 189 he supplies a table for 1861 Cartridge Specifications in which the .69 caliber Musket uses a ball of .65 diameter weighing 412 grains or .94 ounces. The upshot of this is that weighing bullets is an inexact science as there were so many variables at play, but basically the Civil War .69 ball bullet weighed about an ounce.

5 Boothroyd, G., The Handgun, London, 1970. An excellent general survey of handgun history.

6 My thanks to Richard LaVen, who made very careful readings of a draft of this essay as well as correcting the final version. He notes that the Minié ball was a French invention circa. 1851, that was lethal up to four times the distance of a round ball. The illustration Bullets, 1850-1860, Wilcox has scores of profiles and sections of European bullets of this type. Berkeley Lewis ‘Small Arms and Ammunition in the United States Service, 1776-1865’, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol.129, plate 51, Washington DC, (1956)

7 After a year of careful negotiation, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago has approved the author’s course Guns: Myth & Manufacture, which will expand upon the theme of this essay.

8 The development of metallic cartridges occurred simultaneously in France, England and the USA. Patent law was the arbiter for fairness over who would be the beneficiary of the invention, but the niceties of international law were not fully worked out. A design patented in France might not be covered in the USA. Because design concepts were drawn out and described meticulously, agents from competing companies would shop for ideas and patent them as their own in another country. International industrial espionage came to a head in the 1876 International Exposition in Philadelphia, which had a substantial display run by the Ordinance Department of the U.S. Army. It had an operational assembly line from the nearby Frankford Arsenal, and was one of the most popular displays in the Exposition. For the purposes of public relations, the U.S. Army gave away fancy souvenir boxed sets of the stages of manufacture of a .45-70 cartridge, complete with bullet. More importantly they created a display of all the kinds of ammunition that had been developed up to that time. These early cartridge boards were fortunately given to the Smithsonian Museum of American History in 1958 and an annotation and inventory of it written by Berkeley R. Lewis, ‘Small Arms Ammunition at the International Exposition Philadelphia, 1876 in Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, Number 11, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972. Lewis notes that his essay is based upon the excellent Digest of Cartridge Patents, 1878, compiled by Bartlett and Galletin of the U.S. Patent Office, an indication of how proactive the U.S. Patent Office was in bringing foreign patents to the attention of U.S. manufacturers.

9 An excellent essay on Flobert was written by Vorisek, Joseph T., The Flobert Gun, Cornell Publications, (1991)

10 Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, Number 11, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972. pp. 3-8.

11 The Smith & Wesson Patent 27,933 dated April 17 1860, Improvement in Filling Metallic Cartridges places the mercury fulminate only in the rim, thus reducing swelling of the cartridge base that prevented the revolver’s cylinder from turning.

12 Outlines of the patents can be found in Report: Commissioner of Patents for Year (1856), section XIX Firearms and Implements of War, and Parts thereof, including the Manufacture of Shot and Gunpowder. http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/reportofcommis1856unit

13 Richard LaVen, personal correspondence, 07-19-15, pointed out Benjamin Tyler Henry’s contribution to cartridge design.

14 For the early development of Smith and Wesson pistols see, Jinks, Roy G. History of Smith & Wesson, pp. 16-57, Bienfeld, (1977) and Supica, J & Nahas, R, Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, 3rd edition, Gun Digest (2006), pp. 60-63.

15 Richard LaVen remarks, “Black powder is an explosive, igniting with ease and burning with amazing speed, but producing only about 60 % of its weight in gas and 40 % as solid residue. You can only do so much with black powder. You can’t make Super Black. It just does not work. Technically, BP is how explosives are defined. If a substance burns as fast as black powder or faster, it is an explosive. If the substance burns slower than black powder, it is a solid (or liquid or gaseous) fuel propellant. So the early chemists tried to produce a chemically-stable solid that burned at a slower rate than BP, but at the same time gave off much more gas (97 %+) and much less residue. In decreasing the % of solid residue, they got rid of the smoke, but that was really a side benefit.”

16 The Smith & Wesson Number 3 went through several modifications. The last major change was the ‘Schofield’ that hinged the top-latch on the frame rather than the barrel, which meant that a cavalryman could reload the revolver more easily whilst still holding the reins of his horse.

17 Richard LaVen, personal correspondence, 07-19-15.

18 Richard LaVen, personal correspondence, 07-19-15.

19 Richard LaVen remarks, “The .44 Henry rimfire was really a .44 with a nominal bullet diameter of .438”. But the .44-40 Winchester uses .427” bullets, smaller in diameter than the S&W series and if you round up, it’s another .43. Once again, the .44 designation is another marketing ploy.”

20 Richard LaVen, personal correspondence, 09-28-15.

21 Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, Number 11, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972. pg. 42.

22 Richard LaVen, personal correspondence, 07-30-15.

23 Brig. Gen. John Pitman, Ordnance Officer in the United States Army for thirty-nine years, assembled notebooks in which he drew, recorded and added military reports concerning firearms and their ammunition. Facsimiles have been produced of his notebooks The Pitman Notes on U.S. Martial Small Arms and Ammunition 1776-1933, Vol Two Revolvers and Automatic Pistols, edited by Paul E. Klatt, Thomas, Publications, (1990). This volume illustrates most of the guns referred to in this essay, and includes the full ‘Report of Board on Tests of Revolvers and Automatic Pistols’ of 1907.

24 http://www.forgottenweapons.com/wp-content/uploads/manuals/1907pistoltrials.pdf

25 During WWI, when the US Army could not get enough Colt 1911 semi-auto pistols that used the new rimless .45 ACP round, Smith & Wesson invented the half-moon clip that allowed the rimless .45ACP to be used with their Hand Ejector swing out revolver and called it the M1917. It is an interesting moment in design, as a new cartridge is adapted for an existing firearm. This had been done before with the cap & ball percussion revolvers that were re-machined to accept metallic cartridges, but in this case only a tiny metal spring steel form was needed to solved the problem, in addition to shaving off 1/16” from the cylinder to fit it in place.

26 Richard LaVen remarks, “The term “Magnum” comes from the wine industry and refers to the heavy glass bottles used for champagne. The bottles had to be stronger than standard to withstand the internal pressure of carbonated wine. IIRC, the term was introduced into ammunition by Holland & Holland (high quality British gun makers) about 1910-1912. They marketed ammunition with large powder charges and heavy (& stronger than normal) cartridge cases for the wealthy chaps who hunted African animals.”