COLLAGE MAKING

COLLAGE THINKING

Amongst the arsenal of thinking methods,

the process of collage making, though pervasive, occupies a

disruptive position by using trash and deadness to form beauty.

Collage is part of everyone's experience and, however well it is

understood, it seems to refer to a group of ephemeral things

brought together by a logic that disturbs, or negates, the

status of the individual elements. Throughout the passage of

each day, millions of manufactured objects are encountered whose

sheer quantity and variety threatens to outclass nature for

diversity. Collage permits a silent rapport between the

collagist and those objects whose purpose is often too difficult

to comprehend. Collage making allows anyone to hold a view on

any subject. It counters monopoly and it terrorizes guilds of

knowledge. Every professional academy, institution or

organization is vulnerable to collage, as orders of logic are

broken apart by the collagist. Access is gained to information

which is then reordered so that it 'sits right' into the

collagist system of thinking, oblivious of the accepted status

quo.

A

trained collagist requires the act of collage making to be

contemplative. He knows that there is something within the soul

that longs to come forward, so he engages in collage making to

advance it. To express this longing all the printed ephemera,

forming the mirror world of modern existence, is mustered for

use. Thousands of pictures of things varying in scale and

perspective are conscripted to trigger trains of thought,

comprehensible or not. Bibliomanic safaris, considered off

limits in respectable scholarship, are taken through trashy

magazines, high-brow periodicals or well-loved books. The

knife-toting traveler performs transgressive voyeurism that is

wholly satisfying and rarely sanctified. Profanities can be

quarried that the intellect ought not touch. Pictures are

snipped without care for their actual context. Now they are

readied for action. Pages are severed from publications just

because, and all these acts are done to readjust the pictorial

world to suit the viewer a little better.

A

trained collagist requires the act of collage making to be

contemplative. He knows that there is something within the soul

that longs to come forward, so he engages in collage making to

advance it. To express this longing all the printed ephemera,

forming the mirror world of modern existence, is mustered for

use. Thousands of pictures of things varying in scale and

perspective are conscripted to trigger trains of thought,

comprehensible or not. Bibliomanic safaris, considered off

limits in respectable scholarship, are taken through trashy

magazines, high-brow periodicals or well-loved books. The

knife-toting traveler performs transgressive voyeurism that is

wholly satisfying and rarely sanctified. Profanities can be

quarried that the intellect ought not touch. Pictures are

snipped without care for their actual context. Now they are

readied for action. Pages are severed from publications just

because, and all these acts are done to readjust the pictorial

world to suit the viewer a little better.

Then the splicing together of this unique

selection of things can begin. Acts are turned against pictorial

depictions, recognizable or not. Things are done to pictures

that have always wanted to be done but, because of

circumstances, they never took place. Fifteen handles can be

attached to a frying pan with a few deft strokes of a scalpel.

Fingers can be repositioned so that they grow out of ears. Then,

depending on interest, skill and the dexterity of the fingers,

thoughts can be articulated. When the work is complete, a map of

hunches exists and, due to entirely to the act of making, the

soul is temporarily exorcised of what appeared to be coagulating

within. Like all maps, collage can exist as a guide to what

exists on the ground or it can prompt a new set of thoughts

suggested by interconnections of terrain and cities. When

considered from this angle, the collage becomes a transcription

that can accelerate the way one understands the everyday world

and how it comes together, without necessarily being an expert

of any particular field of knowledge.

COLLAGE

TRADITION

If collage is described as the placement

of a fragment next to a similar fragment and then the two are

spliced together in such a way that the net result is greater

than the sum of the parts, one might wonder how this differs

from any other artistic activity. An investigation of sixteenth

or seventeenth-century painterly techniques reveals a picture

perfect world that challenges the veracity of Fuji film and the

Pentax camera. A close examination of the assembly of a painting

shows that the apparent reality of the work is wholly

premeditated. No arm or leg can be moved without upsetting the

balance of the entire composition. Study sketches of paintings

can reveal the a figure might be a composite of different parts

from different people and various fragments of sculpture drawn

from antiquity. Conceptually, a collage is an aggregation of

various pieces which create an irresistible spectacle in the eye

of the maker. Artists of the pre-printing age mentally

transferred items from other sources through drawing. In this

way the artist himself became his own fund for observation.

Similarly, the printed page has become a fertile ground for the

collagist of the printing era where the source of pictorial and

ephemeral views of the world, when he draws it daily, as it

appears in all its dimension.

It is necessary for an artist to use raw

material that is directly associated with the age in which he

lives. It is senseless for a modern city dweller to perform cave

painting using wood dyes and ground rocks as pigments. Drawing,

upheld as the fastest and most direct way to transfer thought,

is a questionable form of representation given the mounting

schism between electronic simulation and the tactile world which

we walk amongst and touch each day. This schism is fast coming

to a crisis as enhanced mechanical senses, independent of each

other, appear to work better than the natural senses that are a

part of the body itself.

The printed page, with its panoply of images of

implied moments of activity, is still the most formidable

depiction of Western life. Correspondingly, the preferred method

of shopping in the U.S.A., since the introduction of the Sears

Catalog in the nineteenth century, is to leaf through scores of

magazines illustrating objects earmarked for purchase. Catalog

shopping is preferred to handling in judging objects'

comparative worth. If this is the contemporary way of producing

and conceiving, then is not wholly correct for the thinker-maker

to use these very same devices - printed catalogs - as the

medium and raw material for an undertaking?

Once pieces are assembled from one source

or another, collage permits extraordinary juxtapositions to

occur. Initially, the activity calls for something to be done.

Picture a lavatory seat that is photographed from an oblique

angle. Then a flurry of cutting and adjusting dictates that the

only object that looks right with the lavatory is a pair of red

scissor handles, half-obscured be the sleeve of a woolly

sweater, all jammed between the seat and its hinged lid. Then a

bigger pair of scissors is stuck between the seat and the side

of an iron. The scissor handles and seat are then covered with a

nicely done rasher of bacon. Why does this particular

juxtaposition seem to be at same moment correct and haunting?

The production of something that is unintentionally both

haunting and surprising may be the very thing that collage makes

possible which other media of expression cannot because of their

techniques. Painting and drawing require every mark on the

canvas to pass through the fingers of the artist. Collage

making, on the other hand, cannot fully control what occurs in

the juxtapositions because it uses ready made components. Unlike

the pencil user, the collagist is introduced to further sets of

ideas which simultaneously transcend the merely contemplative

and go beyond traditional instruments of artistic

expression.

COLLAGE

SCRUTINY

The activity of collage, like every

visual activity, can profoundly alter the way things and places

are viewed. Initially, a collage may be captured by the eye of

the observer and then reduced in consequence by being

categorized amongst things that have the appearance of collage.

But if the observer looks beyond this appearance, the collage

suggests a method of scrutinizing things that is identical to

the disposition within a collage. In one of his collages, Max

Ernst depicted a human-sized slug spread out on a couch in front

of which are distracted musicians. After one has seen this

collage it is never again possible to see someone reclining on a

couch without a slimy afterimage.

In collage the appearance of a subject

may be severely altered, so much so that the individual

characteristics of each component are only barely recognizable

through conventional means. If a collage is constructed of

pieces of paper that combine an unlimited number of perspectival

angles and scales produced by the lens of a camera or the hand

of the draftsman, the observer (and certainly the maker) will

find it difficult to look at familiar things in quite the same

manner. A component of an artist's work is to reveal ways of

comprehending things that are often difficult to assimilate.

These depictions, however abrasive to the eye, reform the actual

appearance of things. It is well to remember here Picasso's

response to critics who condemned his painting ability on the

grounds that his portrait of Gertrude Stein did not resemble the

subject: "In time, she will." He said.

Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye reveals how

the painter's eye, activated by Cubism, can make a piece of

architecture in the same way that a painting is assembled. When

viewed from the outside, the long window on the middle level

frames a bundle of odd, planar shapes. When these shapes are

encountered inside the building the space initially worked out

through painting is then projected on to the flat frame of the

window and finally realized in three full dimensions on the

inside of the house. The collagist-architect has the same access

to the spatial possibilities as does the Cubist painter and can

induce space in the manner that it is experienced through

collage making.

THE ACTIVITY OF COLLAGE MAKING

Collage making can be a very exacting

activity requiring a steady hand to locate the smallest whiffs

of paper in the right position. The collagist's tools are

simple: a scalpel used in tandem with a probe or a pair of

tweezers and small tabs to keep things in the right place prior

to the gluing operation. Whilst the activity takes place the

collagist's table has the same suspense as the surgeon's

theater. Cutting, implanting, temporary clamping and adhesion

all play a role in the proceedure for making a new being.

Certain pieces may have to be spliced in and then covered over

by a complex layer of interconnecting components. The fingers

have to move deftly to prevent the glue from drying too fast.

The activity requires that the work concentrates on the tip of

the knife and the practitioner must have the skill to free the

weight of the body, so that it can pirouette about the scalpel

blade whilst constant direction and pressure is applied to its

point.

During the construction of a collage a small

voice within quips: "scalpel...probe...sutures...swab the glue,

nurse!" The analogy with the surgeon reminds us of the

alchemist's act of blowing life into inert substance. After the

surgeon operates on a supine body, it rises and staggers away in

a half-drugged state with its lease on life temporarily

extended. The collagist operates to reassemble a flat being and,

as with the great collagist Dr. Frankenstein, something is

brought to the quick that did not live before. The collagist

holds the secret to making things out of thin paper. Things that

formally existed in some other state are subsequently

transmuted.

The procedure of collage making, the very

way that the collage is put together, takes place as a series of

passes, each one forming a layer or varnish that must be carried

out in a certain order for the effect to work correctly. The

first act, book rape, is the most violent because it ruffles the

status quo that is embedded within us. Book rape involves the

deliberate procurement of a document representing a major part

of an author's life then slashing it into little pieces, a

method reminiscent of the voodooer sticking pins into a wax

effigy. The book is quarried for parts, its original order

revamped into a pile of paper rounds that have the potential of

being reordered. Once there is a sheaf of ephemeral devices the

grand fidget begins. This reforms the pieces into something that

amounts to more than their torn edges alone can effect.

The placement of paper pieces is a

desperate act. Unless the first association works, all

subsequent layers of activity will do little to hide the

inadequacy of the first move, its prime flourishing. A piece of

a picture is set down and then another is squinched under, over

or spliced into it. Imagine a pair of door-like forms next to

each other. (See The Sagittal Name Collage) For them to be

complete they require a squiggle on their kick plates. There is

only one spot on the doors where the squiggle can go that is

mutually acceptable to both doors. Each portal forces the

squiggle around until it nestles into the tightest spot. It is

possible to watch the squiggle on the end of the scalpel move

until it finds the best location. The hands become tools to aid

and abet its placement, they do not cause it. What determines

their correct positioning is a question difficult to answer. If

found, the answer would instill a terror-knowledge akin to

hubris. Collage making allows for a myriad of yes/no decisions (

it is a binary process) to determine where the fragments should

go. Because this method involves working with papery objects,

rather than pencil, countless irrevocable moments occur: moments

when it must be decided if a piece of paper has to be glued

either her or there.

The speed

of decisions regarding the correct juxtaposition of the paper

pieces will be slowed by the contemplative mechanical process of

splicing the papers into each other, so as to make their

conjunctions read more effectively. Then the process of placing

things next to each other becomes more akin to the drawing

process, for the two pieces of paper slowly approach and nudge

each other until they fit in with aplomb.

The speed

of decisions regarding the correct juxtaposition of the paper

pieces will be slowed by the contemplative mechanical process of

splicing the papers into each other, so as to make their

conjunctions read more effectively. Then the process of placing

things next to each other becomes more akin to the drawing

process, for the two pieces of paper slowly approach and nudge

each other until they fit in with aplomb.

Once the fragments find their rightful

places, the collage can appear to be so correct that it becomes

bland. It has lost its spirit, since all the tensions are

pushing and pulling with equal force. When this occurs the

pieces have to be minutely calibrated, taken off-center, to

recharge the vitality that surrounds their mutual conjunction.

The process of placement of two unlikely objects next to each

other causes a pain equal to the sigh of relief released by

their new found proximity. The ability of the hands to make

nonsensical judgments and the irrationality of these adjustments

point to the existence of moments of unerring correctness in

matters that are not clearly understood.

A collage cannot be ghosted into

existence as a drawing. The activity of drawing often lays down

spines on paper which are slowly covered by further, more

decisive lines until the likeness of the drawing is formed.

Collage, instead, might form islands of material which could be

covered over with other pieces, sometimes translucent,

permitting the temporal layers to be simultaneously revealed.

Collage can be assembled in a manner that reflects the sense of

coexistence of urban living. A fragment of marked paper can rely

upon its neighbor for conversation, its neighbor's neighbor and

its neighbor's neighbor's neighbor, happy in the knowledge that

they're there.

THE

TECHNIQUE OF THE COLLAGE

Placing a

tiny bit of paper next to another in a sequence implies that

once it is placed in a particular spot it will not move. The

associations are so dependent on slight movement that 1/64 inch

will account for ins rightness or wrongness. Prior to

gluing,each piece of paper is held in place by homemade tabs of

drafting tape measuring 1/16 by 3/32 inch These sutures are

continually lifted and replaced permitting other components to

be spliced into each other.

Placing a

tiny bit of paper next to another in a sequence implies that

once it is placed in a particular spot it will not move. The

associations are so dependent on slight movement that 1/64 inch

will account for ins rightness or wrongness. Prior to

gluing,each piece of paper is held in place by homemade tabs of

drafting tape measuring 1/16 by 3/32 inch These sutures are

continually lifted and replaced permitting other components to

be spliced into each other.

How do six pieces of paper that weave into each

other at a common spot get glued? If one piece is irrevocably

glued, then it is not possible to slide a piece under it to link

up with something else. But despite all this the pieces do get

glued. Consciously gluing something in the wrong order is done

out of desperation to make an inroad into a mat of

impossibilities. It is an activity that requires the collagist

to glue anything that seems to not rely upon something else, a

muculous anarchy. Once the illogical move is made the gluing

continues as if nothing had happened at all. Making requires

living with something that is knowingly incorrect. It is this

anti-idealistic incorrectness which mysteriously permits the

work to advance. If any moment of the collage making process

constitutes spontaneous combustion, it is this. The quick drying

glue sets the pace, hands and tools whistling along without

stopping until it is completed. The procedure can be likened to

a dental assistant's act of swapping probe for drill, without

exchange of words. It is the choreographic interchange in a work

of art --whether between one's own hands or between a collection

of hands--that proves its self-worth.

Once this battle has been played out, the terrain of

a collage appears exhausted. Pieces of paper bear crease marks

where they have been contorted, their edges are scuffed. The

knife-edge precision of the work, prior to gluing, is dulled and

must now be restored. Critics have condemned the recent process

of cleaning the Sistine Ceiling, arguing that Michelangelo's

touch-up brush strokes have been obliterated by the restoration.

What appears in the restored ceiling is the work without the

discretionary adjustments of the artist that trim out the work,

adjustments that are not possible to include in the frantic

immediacy of the making. So that it speaks with a clear voice,

collage, as with all endeavors, requires this final pass of

cosmetic adjustment.

Once this battle has been played out, the terrain of

a collage appears exhausted. Pieces of paper bear crease marks

where they have been contorted, their edges are scuffed. The

knife-edge precision of the work, prior to gluing, is dulled and

must now be restored. Critics have condemned the recent process

of cleaning the Sistine Ceiling, arguing that Michelangelo's

touch-up brush strokes have been obliterated by the restoration.

What appears in the restored ceiling is the work without the

discretionary adjustments of the artist that trim out the work,

adjustments that are not possible to include in the frantic

immediacy of the making. So that it speaks with a clear voice,

collage, as with all endeavors, requires this final pass of

cosmetic adjustment.

COLLAGE: THE IMPLICATIONS BEYOND

ITSELF

The moment after collage making is filled

with anticipation. One sort of closure is confirmed, for the

work is done, but a further activity enforced by self-critical

distance lingers on. Tactile thoughts are articulated that

formerly existed only in the shape of grunts and gesticulations.

When finished, it is possible to see what issues need to be

addressed which were invisible before the making. Only by the

continued repetition of the act of making can the initial doubts

raised by the work be dissipated.

Collage is an interstitial state: neither flat

nor round, neither identifiable not chaotic. When objects

snipped from magazines are reformed into an ephemera of collage

they transcend their former pictorial candor. The identity of a

frying pan might be lost but its associated smells still linger.

The task of collage is to regurgitate the frying pan enough

times so that the metal is worn away but its patina is left

intact.

Gazing at a collage, in a shadow-filled

light, immediately lifts the work from flatness. Because paper

has thickness, albeit paper thin, the collage is a relief.

Drawing, the activity which exists within a sheet of paper, is

reluctant to build up layers of graphite on the surface. The

weight of the pencil stroke overwhelms the graphite and the

pencil line is scored in the surface of the paper. In a work of

art, relief is the very first glimpse of roundness. Whilst

shadows are drawn in drawings, they are cast in three dimensions

in collage relief. Because of the thinness of paper, collage

relief also permits translucence. Light is reflected off a

surface that is apparently hidden beneath a covering surface.

Thus, a collage is the first hint at a condition for fullness

that can exist after the substance of artistic intent has

removed itself from the flattened surface of the canvas. The

relief created by superimposition can be read as a talisman, as

an indication of its three-dimensional qualities. Were the

collage to become an object in space, its structure would inform

the way it is to be built.

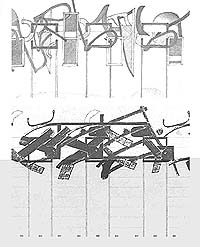

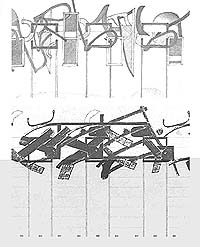

The collage method used to form the

Appliance House adopts a pungent chopping technique and asks

that every junction be highly considered, that each round of

collaging, each pass, involves a pictorial dissolution of the

depicted object as well as structural reassembly. With this

obfuscation in mind, it is possible to take the collage,

challenge its status once again and cut it up providing material

for a new collage, a new work. The process is then repeated to

make a third collage. In the third state of obfuscation the

original objects are virtually unrecognizable. Instead, the

increasingly complicated junctions between paper fragments take

precedence over the images depicted on the paper. The status quo

of the frying pan is abandoned. It is emptied of pictorial

content. It wishes to stake out the perimeter of its own rim

without touching its edge or seeing a reflection within

it.

This desire to locate something that is

not known can be confused with the expectation of creating

something that eludes forewarning or prediction. Ultimately,

both intentions - the unpredictable and the hankering after the

elusive status quo of the heart strings - fold into a single

cause which collage understands intimately. By peeling itself

off the paper surface, collage can be brought into relief, the

round, the hollow and on into the construction of a

building.

A

trained collagist requires the act of collage making to be

contemplative. He knows that there is something within the soul

that longs to come forward, so he engages in collage making to

advance it. To express this longing all the printed ephemera,

forming the mirror world of modern existence, is mustered for

use. Thousands of pictures of things varying in scale and

perspective are conscripted to trigger trains of thought,

comprehensible or not. Bibliomanic safaris, considered off

limits in respectable scholarship, are taken through trashy

magazines, high-brow periodicals or well-loved books. The

knife-toting traveler performs transgressive voyeurism that is

wholly satisfying and rarely sanctified. Profanities can be

quarried that the intellect ought not touch. Pictures are

snipped without care for their actual context. Now they are

readied for action. Pages are severed from publications just

because, and all these acts are done to readjust the pictorial

world to suit the viewer a little better.

A

trained collagist requires the act of collage making to be

contemplative. He knows that there is something within the soul

that longs to come forward, so he engages in collage making to

advance it. To express this longing all the printed ephemera,

forming the mirror world of modern existence, is mustered for

use. Thousands of pictures of things varying in scale and

perspective are conscripted to trigger trains of thought,

comprehensible or not. Bibliomanic safaris, considered off

limits in respectable scholarship, are taken through trashy

magazines, high-brow periodicals or well-loved books. The

knife-toting traveler performs transgressive voyeurism that is

wholly satisfying and rarely sanctified. Profanities can be

quarried that the intellect ought not touch. Pictures are

snipped without care for their actual context. Now they are

readied for action. Pages are severed from publications just

because, and all these acts are done to readjust the pictorial

world to suit the viewer a little better.

The speed

of decisions regarding the correct juxtaposition of the paper

pieces will be slowed by the contemplative mechanical process of

splicing the papers into each other, so as to make their

conjunctions read more effectively. Then the process of placing

things next to each other becomes more akin to the drawing

process, for the two pieces of paper slowly approach and nudge

each other until they fit in with aplomb.

The speed

of decisions regarding the correct juxtaposition of the paper

pieces will be slowed by the contemplative mechanical process of

splicing the papers into each other, so as to make their

conjunctions read more effectively. Then the process of placing

things next to each other becomes more akin to the drawing

process, for the two pieces of paper slowly approach and nudge

each other until they fit in with aplomb.

Placing a

tiny bit of paper next to another in a sequence implies that

once it is placed in a particular spot it will not move. The

associations are so dependent on slight movement that 1/64 inch

will account for ins rightness or wrongness. Prior to

gluing,each piece of paper is held in place by homemade tabs of

drafting tape measuring 1/16 by 3/32 inch These sutures are

continually lifted and replaced permitting other components to

be spliced into each other.

Placing a

tiny bit of paper next to another in a sequence implies that

once it is placed in a particular spot it will not move. The

associations are so dependent on slight movement that 1/64 inch

will account for ins rightness or wrongness. Prior to

gluing,each piece of paper is held in place by homemade tabs of

drafting tape measuring 1/16 by 3/32 inch These sutures are

continually lifted and replaced permitting other components to

be spliced into each other.

Once this battle has been played out, the terrain of

a collage appears exhausted. Pieces of paper bear crease marks

where they have been contorted, their edges are scuffed. The

knife-edge precision of the work, prior to gluing, is dulled and

must now be restored. Critics have condemned the recent process

of cleaning the Sistine Ceiling, arguing that Michelangelo's

touch-up brush strokes have been obliterated by the restoration.

What appears in the restored ceiling is the work without the

discretionary adjustments of the artist that trim out the work,

adjustments that are not possible to include in the frantic

immediacy of the making. So that it speaks with a clear voice,

collage, as with all endeavors, requires this final pass of

cosmetic adjustment.

Once this battle has been played out, the terrain of

a collage appears exhausted. Pieces of paper bear crease marks

where they have been contorted, their edges are scuffed. The

knife-edge precision of the work, prior to gluing, is dulled and

must now be restored. Critics have condemned the recent process

of cleaning the Sistine Ceiling, arguing that Michelangelo's

touch-up brush strokes have been obliterated by the restoration.

What appears in the restored ceiling is the work without the

discretionary adjustments of the artist that trim out the work,

adjustments that are not possible to include in the frantic

immediacy of the making. So that it speaks with a clear voice,

collage, as with all endeavors, requires this final pass of

cosmetic adjustment.